Thank you for the comments. I really appreciate it.

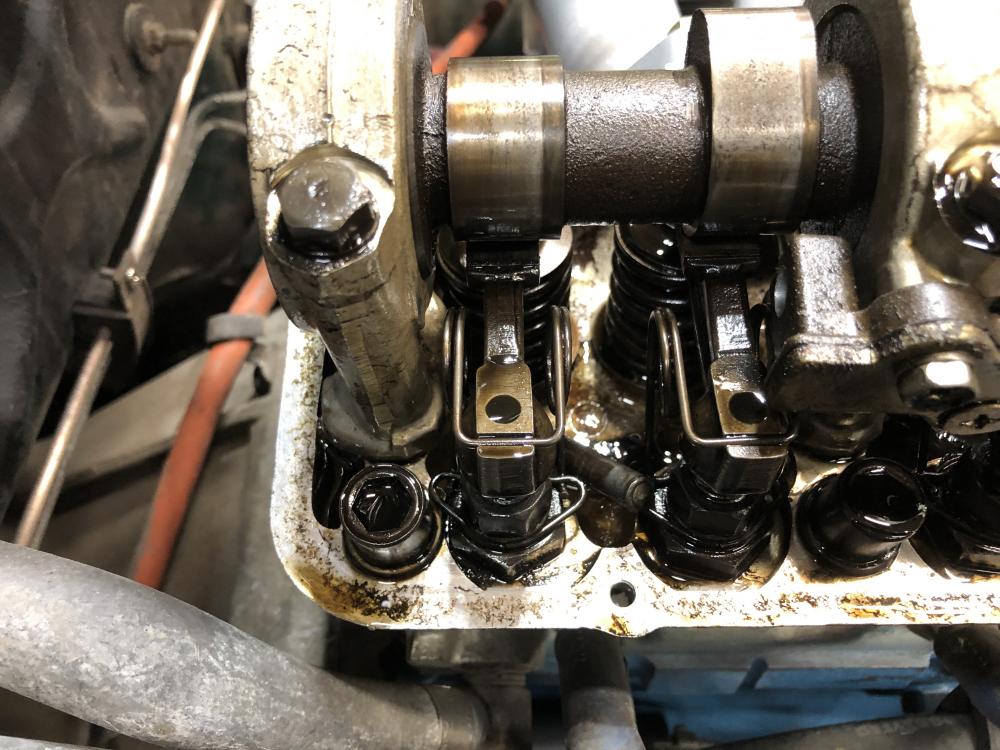

That thing took about every bit of a day and a half to make. Started with the flat area and marked the opening cutouts. Then I used a scribing tool to mark the length of the turndown flanges. I just set the gap to about .210 and ran it around the inside of the openings to get the cut lines. Used a jigsaw and die grinder to cut make the cutouts to the offset lines.

I used a lot of things in the shop that were never meant to be beat upon as a backup rest for the metal while I slowly tapped the flanges down. The big problem is that flat section needs to be held hard and flat while you are working the flanges down. Because the flanges are so short, the metal is really hard to work (no leverage + work-hardening), and the flat area around where you are working it wants to deform upwards in reaction to the flange being deformed down by the hammer. I did the best I could to use clamps or heavy pieces of steel to try to keep things in place, but it wasn't good.

So I started using a little heat right on the flanges because they had to stretch as they make the curves. That helped a lot, but not really enough, because the flanges didn't really want to stretch enough. I was reluctant to add too much heat as I didn't want the flat area to easily deform - I wanted them to stay hard and flat. At some point I used steel tubes and rounds of the correct diameters as forming tools where I pounded the rounds into the openings to force the flanges to stretch enough and make the profiles look halfway correct. That also helped a lot, but if you look at the radiused openings they don't quite look right still because the flat sections started to deform under the stress of the round "forming tools". So then I had to go back and reflatten the flat areas.

The biggest problem with forming the short flanges is that after you've formed the first one, it is now in the way of getting all the others done. You have to have a piece of steel you can hammer against, it has to be large enough for the area you are working, it has to be small enough to fit between the previously formed flanges and you have to have a way to clamp it to something solid. I have an anvil, dollies, lots of scrap steel, a million clamps, many hammers, and yet I still had trouble getting it all to work together.

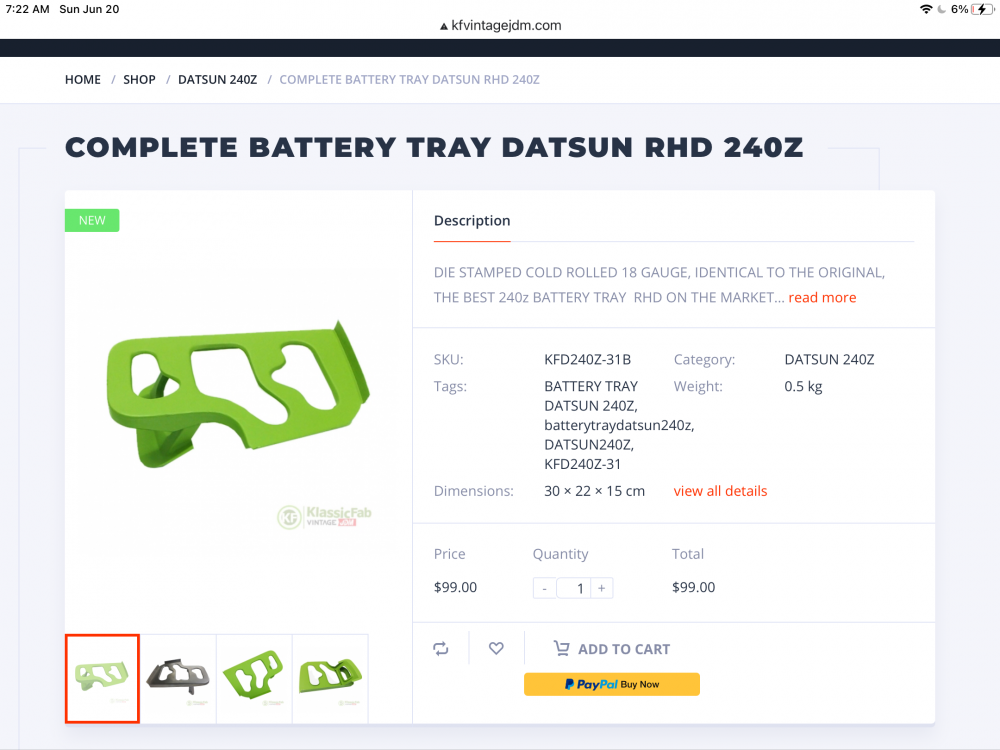

We were having having beers with friends yesterday at a great outdoor place overlooking a portion of the Shenandoah Valley. My buddy used to make the bodies for his race cars, so I kept quiet and let tell me how to do it. "Ahh, it's easy - you just need a positive and negative form." Really? Why didn't I think of that? Of course I need forms 😁. So there's the challenge. Make forming tools. Those curves are organic. It's totally doable to make in wood using a handheld router, but it would some slow and very careful work. But at .062, CRS is going to win against wood (unless it's perhaps Ipe), when you start bending those short flanges against it. I could also go back to .047 which would make a huge difference. In fact, with a little thought to adding stiffening gussets to the underside and securing the batery well, 20 gauge (.035) would do the job.

As for the larger flanges, all straight sections are bent, including the two upturned flanges, one of which is curved. All the corners for the downturned flanges are welded on. After everything was in place and welded up, I used a air board file with ceramic abrasive to level off the bottom of the cutout flanges. That made a huge difference to the appearance of the underside; although, you'll notice I didn't show a picture of the bottom of the shelf. Between all the various hammer, chisel, and blunt objects marks, welds I couldn't quite get to grind to my satisfaction, and the bluing from heating, it looks a little rough. Maybe a little spray-on flaw remover (undercoat/bed liner/body filler) would help 😉

Subscriber

Subscriber 4Points3,747Posts

4Points3,747Posts